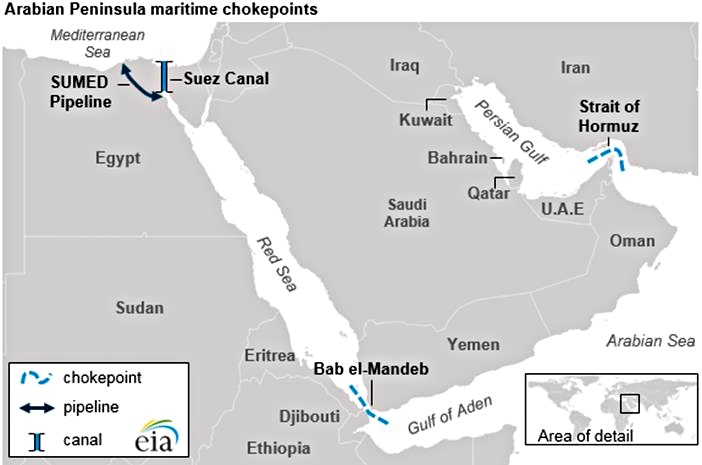

While everyone has been watching the Strait of Hormuz amid rising tension between the U.S. and Iran, a chokepoint on the other side of the Arabian Peninsula is now at the center of attention.

Last month’s reported attack by the Houthi rebels in Yemen on two Saudi oil tankers in the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb and Saudi Arabia’s suspension of oil shipments through the strait have demonstrated how vulnerable the world’s key oil chokepoints are and how easy it is to disrupt global oil traffic.

Four key world chokepoints of oil, namely the straits of Hormuz, Bab al-Mandeb and Malacca and the Suez Canal account for two-thirds of global oil trade traffic. Almost 45 million barrels of oil travel daily through these chokepoints.

Through the world’s most vital chokepoint, the Strait of Hormuz, 18 million barrels of oil or 27 percent of oil traffic and a third of global LNG supplies, pass every day. Oil exports from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar (including large volumes of LNG exports), the UAE and Saudi Arabia must pass through the strait. All of them with the exception of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia will not be able to export any oil if the Strait of Hormuz is closed or mined.

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have pipelines that circumvent the Strait of Hormuz. Saudi Arabia has the 750-mile Petroline (or East-West Pipeline) which runs across the kingdom from the east to the west at the Yanbu port on the Red Sea. Through the Petroline, with a capacity of 4.8 million barrels a day (mbd), some Saudi oil could bypass both the straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandeb, linking up with tankers at Yanbu port and from there toward the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean.

The UAE has the Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline, which has a capacity of 1.5 mbd. The pipeline runs from the Habshan onshore field in Abu Dhabi to Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman, bypassing Hormuz.

Iraq is totally dependent on the Strait of Hormuz for its oil exports since the Iraqi-Turkish pipeline known as the ITP transporting Iraqi oil from Kirkuk to Ceyhan on the Turkish coast on the Mediterranean is currently out of action.

Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar have no alternative but to use the Strait of Hormuz. Meanwhile, Iran is building an oil export pipeline on its southeastern coast beyond the Strait of Hormuz expected to be operational by the early 2020s.

The Strait of Bab el-Mandeb is a narrow passage connecting the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea with the Mediterranean.

This chokepoint sees just under 5 mbd of oil traffic, but its importance is magnified for two reasons. First, most oil that has to pass through the Suez Canal/SUMED pipeline must first pass through the Bab el-Mandeb. Second, it is, at this point, close in proximity to the war in Yemen.

There are no alternatives to the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, except for the Saudi petroline. A closure of the Strait would force tankers to travel around Africa’s southern coast.

A third major chokepoint is the Suez Canal. Combined with the SUMED pipeline which bypasses the canal and connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, the two routes account for 8 percent of the world’s daily seaborne oil, or 5.5 mbd. Most of the oil goes north from the Middle East to Europe.

The Suez Canal cannot handle the largest oil ships, ultra-large crude carriers (ULCCs). It can only handle very large crude carriers (VLCCs) when not fully laden. As such, VLCCs can deposit some of their cargos onto the SUMED pipeline and then the lighter ship can pass through the canal, picking up the oil at the other end of the pipeline on the Mediterranean. The SUMED pipeline can carry 2.34 mbd and offers a hedge of sorts against an outage at the Suez Canal. It is the only alternative route that can bypass the Suez Canal otherwise tankers would have to travel around the southern tip of Africa.

The second most important chokepoint in terms of oil volume is the Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Malaysia. More than 16 million barrels of oil pass through it daily.

The strait is only 1.7 miles wide at its narrowest point, creating a natural bottleneck with the potential for collisions, grounding, or oil spills. China, the largest oil importer in the world, has a strategic interest in seeing uninterrupted tanker traffic through the strait.

China is overwhelmingly dependent on the strait as 80 percent of its oil imports pass through it. The strait links the Indian and Pacific oceans, and is the main route for oil from the Middle East to reach Asian markets.

China’s growing dependence on oil imports has created an increasing sense of “energy insecurity” among Chinese leaders.

With the American navy patrolling the southern end of the Strait of Malacca and the Indian navy patrolling the northern end, China feels sandwiched in and strategically vulnerable. The former president of China, Hu Jintao, has referred a number of times to what he describes as the “Malacca dilemma.”

China’s answer to the “Malacca Dilemma” was the newly-opened China-Myanmar crude oil pipeline.

The 479-mile-long oil pipeline runs from the port of Kyaukpyu on Myanmar’s west coast and enters China at Ruili in Yunnan Province. It loads oil shipments from the Bay of Bengal and ships it to China’s Yunnan province. The pipeline with a capacity of 442,000 b/d bypasses both the straits of Hormuz and Malacca.

Iraqi crude oil for instance could be shipped from Ceyhan on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast and from there through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean instead of through the risk-prone straits of Hormuz and Malacca before reaching Myanmar and entering China.

By and large, the alternative routes to these major chokepoints are only partial solutions, if at all. A closure of any of the four chokepoints for a lengthy period of time could send oil prices far above $150 a barrel.

Iran has threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz if it was prevented from exporting its crude oil as a result of U.S. sanctions, and this threat should be taken seriously.

The strait at its narrowest point is 21 miles wide so it is militarily impossible to close it completely. Iran could mine it stealthily with the expectation of a mine hitting an oil tanker and sinking it. Such an accident in itself would deter tankers from crossing the strait, thus causing a disruption in oil supplies until the mines are cleared.

Alternatively, Iran could threaten sinking tankers crossing the strait even if escorted by the U.S. Fifth Navy in the Gulf. This threat might deter tanker owners around the world from sending their tankers across the strait under pressure from global insurance companies until tension has subsided. In this way, Iran would have achieved its goal of disrupting oil supplies peacefully.

The Strait of Malacca at its narrowest point poses a natural bottleneck which could be blocked by a collision of two ships or even the sinking of one.

Because of its small width, the Suez Canal is the easiest to block by a sinking of even a small vessel.

*Dr Mamdouh G Salameh is an international oil economist. He is one of the world’s leading experts on oil. He is also a visiting professor of energy economics at the ESCP Europe Business School in London.

Hello, the comments you share on our site are a valuable resource for other users. Please respect other users and different opinions. Do not use rude, offensive, derogatory, or discriminatory language.

The floor is all yours.