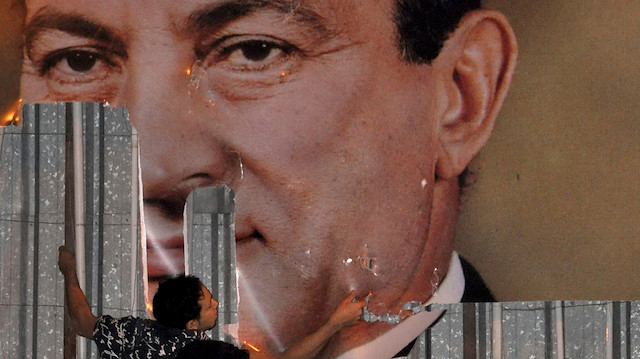

: An anti-government protester defaces a picture of Egypt's President

Two characteristics of longest serving Egyptian leader term were prevalent oppression, corruption

Egypt’s ousted leader Hosni Mubarak died on Feb. 25 at the age of 92.

Born in 1928 to a poor family in Monufia province, Mubarak graduated from the military academy in 1949. Afterwards, he started to get recognized after joining the Egyptian Air Forces.

The young officer closely monitored the coup d'état carried out by Gamal Abdel Nasser with nationalist officers known as the “Free Officers” in 1952 and the immediate transformation.

The defeat against Israel at the end of the 1967 Six-Day Wars threw the nationalist policies into crisis in Egypt, which greatly weakened Egypt's leadership role and influence in the region.

Anwar Sadat, who took over the rule from Abdel Nasser at the beginning of 1970s, assigned Mubarak as the chief of the Air Forces in 1972.

After he played a crucial role in planning of a surprise attack on Israel in 1973, he shone bright and was appointed as the army general. In 1975, he was appointed as vice president by Sadat.

Sadat abandoned Nasser’s approach against the West, and put Egypt in favor of the West.

As in the case of the Camp David agreement with Israel, Vice President Mubarak did not openly support normalization with Israel, but neither opposed it.

Following the agreement signed with Israel, Mubarak personally witnessed harsh reactions from regional communities and other Arab countries against Egypt. As a result, Sadat was assassinated in 1981 and Vice President Mubarak naturally took over his office.

During the 30-year rule of Mubarak that started in 1980s, he adopted the policies of Sadat. He did not cancel the agreement with Israel and established good relations with the U.S. He brought Egypt, which was expelled from the Arab League over the negative influence of the Camp David, back to the Arab political scene, though not to its previous place.

The Saudi Arabia-Egypt relations, which soured during the reign of Nasser, began to normalize during the Sadat’s reign. But, even Saudi Arabia reacted to the Camp David agreement, distancing itself from Egypt.

The Mubarak administration normalized relations with the Arab world and went on to develop close relations, especially with Saudi Arabia. The most important regional development of the Mubarak era was the Iran-Iraq War, which took place between 1980 and 1988. During this period, Egypt supported Iraq militarily and economically against Iran. During the term of Saddam Hussein, nearly one million Egyptian citizens were working in Iraq, which was a highly developed country at that time.

In 1983, he became close to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), giving partial importance to the Palestinian cause. Due to the increasing normalization and its importance that cannot be ignored, Egypt was readmitted to the Arab League in 1989.

Mubarak’s tenure lasted longer than other presidents preceding him in the Egyptian history. The strict security measures and surveillance and inspection methods Mubarak, who survived numerous assassination attempts, used had effect on this.

His own military career and assassination of his successor Sadat, as well as his fear of his own people, played an important role in this security-oriented approach. So much so that there is not even a photograph of Mubarak taken in public. The pictures were always taken in controlled and high-security environments.

Unlike Sadat, Mubarak did not appoint a vice president, as he might have feared a coup in palace during his 30-year rule.

In the 1990s, Mubarak's Egypt played a serious role in shaping the new Middle East by capturing significant opportunities in the post-Cold War era.

The most important of them was the Gulf War against Hussein's invasion of Kuwait. Egyptian troops were among the first to reach Saudi Arabia as part of the Allied Forces. Egypt received financial aid from Gulf states during and after the war, and the U.S., the EU and the Gulf waived its $20 billion debt. Saddam's losing power weakened the anti-Western nationalist camp in the Arab world and brought the Westerner camp to prominence.

An unknown side of Mubarak was his role in the removal of the PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan from Syria with the signing of the 1998 Adana Accord, after Syria was threatened by Turkey for hosting the PKK and he acted as a mediator between Turkey and Syria like Bill Clinton.

Despite the rivalry between him and Hussein, unlike the Gulf states, Mubarak opposed the invasion of Iraq in 2003, saying the Palestinian issue must be solved first.

It was the first time he run against an opponent in the 2005 presidential election, and he won the election with security measures. After the election, he had his rival Ayman Nour jailed for five years. Two main characteristics of Mubarak’s tenure were the prevalent oppression and corruption.

Even though political parties were formed, they were just for show, rather than standing as opposition.

During this period, police harassments against real opponents and the young people, and prison sentences without trial increased. Control and censor on media, universities and mosques mounted.

Just like in all the closed and central administrations, corruption, which already existed in Egypt, continued to pose an important problem. The lack of independent democratic control mechanisms also made it impossible to fight against corruption.

Sadat's expansion policy was also manifested in domestic politics: The Muslim Brotherhood organization (Ikhwan) was allowed to operate in the society without being recognized as a legitimate group. It also continued during the Mubarak administration. He did not hinder the outreach, educational and religious activities of the Muslim Brotherhood; perhaps he could not. The Muslim Brotherhood, which spread in the social base and had influence on student clubs and professional chambers, entered the parliament in 1980s despite all obstacles. Sufi groups were supported and the way was cleared for apolitical Salafist groups to break Ikhwan's influence.

Even though Egypt's economy was liberalized during the Mubarak era, a distorted economic structure was formed as the politics was not liberalized. The Mubarak family and their men saved billions of dollars by corruption, bribery and normal business.

For example, it is said that Mubarak took serious bribes to sell Egyptian natural gas to Israel cheaper than the market price. The Mubarak family was profiting great financial gain by taking bribes from successful companies or as their compulsory partner. Conglomerates that were uncooperative or growing uncontrolled could be bankrupted by the state. Such an unregulated regime had difficulty in attracting investment from outside. This unstable economic environment increased unemployment in the country, while also put workers under legal and economic pressure. After the revolution, the Cairo Court would convict Mubarak and his sons of corruption.

When riots, which started in Tunisia at the end of 2010, brought down the administration of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, strong protests began in Egypt, which was experiencing similar problems.

Father Mubarak, who previously wanted to make his son Gamal Mubarak, the president, did not support his son any more when protests did not stop despite 800 people being killed.

Although he appointed Omar Suleiman as vice president to gain the support of the army, the Egyptian army dismissed Mubarak from the office when demonstrations continued. With this move, which meant a kind of coup, the Egyptian army chose to save the ship (the regime) by sacrificing the captain. But the military regime, which also protected Mubarak, kept him out of sight until he died, preventing him from being harassed.

The two most important topics of Mubarak's foreign policy were security and priority of protecting the current regime. Mubarak stood close to the U.S. and the West in adhering to the Camp David agreement signed with Israel. He continued his cooperation with Israel without appearing much close to it. On the other hand, he developed good relations with the PLO, tried to mediate talks with Israel and assumed a negative attitude toward Hamas.

In addition, Mubarak adopted a negative stance against the Islamic Revolution in Iran, and hosted the ousted shah, and established close ties with the Gulf states. He believed that good relations with the U.S. depended on maintaining good relations with Israel, and preferred to pass on the democratization demands of the Middle East that emerged after the Sept. 11 attacks with a few symbolic changes.

[Prof. Dr. Ahmet Uysal is the chairman of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies (ORSAM)]

#Hosni Mubarak